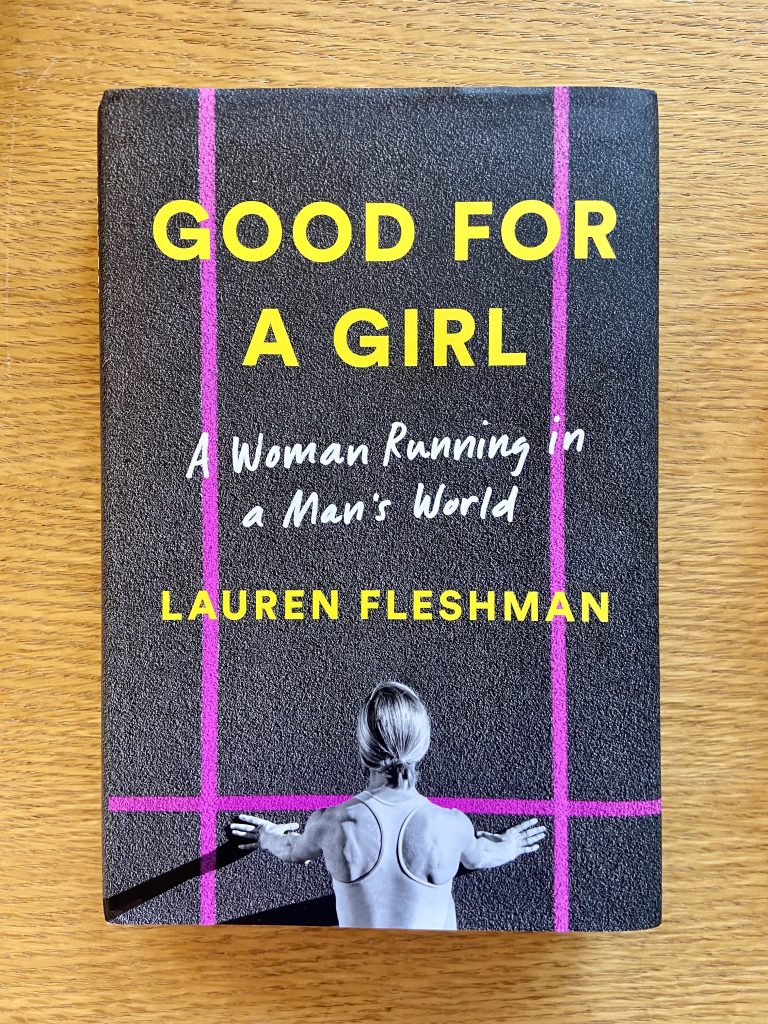

I was thrilled when I first learned that Lauren Fleshman, one of the most decorated American runners in my lifetime, was writing a memoir, Good for a Girl. A few years ago, she published a “Dear Younger Me” essay that went viral, and I think I am responsible for at least half its page views. She was the first person I knew who wrote about the addictive magic of the sport, but didn’t shy away from discussing the dangers of it, particularly for women and girls who get stuck in a cycle of disordered eating when their bodies change, believing the myth that being thinner will make them faster, which inevitably leads to injuries, both emotional and physical. (“There are so many ways to lose yourself in this sport,” she writes hauntingly in Good for a Girl.) As the mother of a competitive runner, I can tell you this was never discussed in locker rooms with high school coaches or in meetings with college coaches the way it should’ve been. Let me rephrase that: It was never discussed at all. Fleshman, who won five NCAA championships for Stanford and two national professional championships, before succumbing to her own devastating injuries, wants to change this. Her book, out today, makes a convincing case that American girls and women are participating in a sports system that is geared towards men and it’s failing them.

As you likely know by now, there are not many things I love more than a running memoir. This is probably because of my daughter and because I’ve run pretty regularly since I was a teenager, too. But also, I think it’s because the same qualities that define great runners — individualistic, introspective, deep-digging, driven — also happen to be the qualities that make great writers. Perhaps the most obvious Exhibit A here is the famous novelist Haruki Murakami. In his slip-of-a-manifesto, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, he writes “the essence of running is about exerting yourself to the fullest within your individual limits: that’s the essence of running, and a metaphor for life– and for me, for writing as well.” In other words, books about running are never really only about running. They’re about self-betterment. The idea that there is always another gear that your body, or your mind, can shift to — even when you’ve got nothing left in the tank — is endlessly fascinating to me. Maybe because it’s also endlessly elusive to me. (Don’t make me show you the splits on this morning’s three miles to prove that point.)

Fleshman continues with this tradition. The early part of her story where she is first discovering her talent and just winning winning winning is what we in the service journalism world might call actionable: So often she made me want to close the book so I could immediately lace up my Hokas. (“I would ramp up my speed until it was impossible to think of anything else but the running,” she writes, “until I wasn’t a girl, or a middle schooler, or in PE class at all. I was just a body, limbs and blood and breath and power. The high followed me out of the locker room into the halls and it grounded me.”) The book is also very insidery (some of my favorite moments were about her sometimes upsetting dealings with the top brass at Nike, including CEO Mark Parker). Ultimately, though, more than inspiring, more than insidery, it’s important.

A few years ago the runner Mary Cain, a young phenom and Olympic hopeful who joined the Nike Oregon Project right out of high school (and who turns up in Fleshman’s book quite often) published a video op-ed for the New York Times chronicling the emotional abuse and body-shaming she suffered at the hands of the legendary coach Alberto Salazar. When the story came up in conversation with a high school track coach a few days later, I’ll never forget what that coach, a guy, said. “What a waste. All that talent and she couldn’t tough it out.” It made my stomach turn thinking of this same guy coaching so many girls. In his defense, he was a full-time history teacher who coached the track team on the side, it’s not like he earned some kind of special certification to get that job. But I have to imagine this is the reality more often than not, and the ignorance is dangerous. There is a scene in Fleshman’s book when she describes being passed in the NCAA cross country championships, a race Fleshman was favored to win. But then, a woman who she had described earlier as sickly thin, “pulled away from the lead pack with an ease that made me feel helpless. Anger and frustration started pressing in on me. She was killing herself and she was going to win the thing, like so many over the years. And every athlete, every coach, would see that and add to the pressure to be thinner. In my mind, that coach who was allowing that athlete to compete while severely ill was hurting her — and the rest of us, too.”

In summation: I want you to read Good for a Girl, but I want your daughter and your daughter’s coach to read it more.

Reminder: All the fun stuff these days happens in the Dinner: A Love Story newsletter on Substack, which is delivered right to your inbox, and is consistently in the Top 10 most-read food newsletters on the entire platform. You can subscribe here.

Thanks for introducing me to this book. I just started listening to Lauren’s interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air, which I can’t wait to finish. This is an essential conversation for parents of athletes, regardless of gender, athletes, coaches, counselors, doctors–basically, all humans. I’m a writer for a digital marketing practice near Seattle, WA, and recently shared a personal presentation with my co-workers about the importance of birth and safe birthing practices. It may not seem related but it represents, to me, the lack of information shared about women’s lives, bodies, and experiences–and their importance. (Sidebar: why do my daughter and I have to worry about running or walking by ourselves???) You have been an important voice in this conversation for a long time and I thank you for that.